Today, December 7, 2014, it is one year ago since the German artist Michael Vetter passed away, shortly after turning 70. Several musical events commemorate the passing away of this visionary artist, who is best known as an overtone singer. Three weeks ago we had a Festival Transverbal here in Taipei, the German radio repeated DuO, a fantastic radio play by Michael Vetter and Natascha Nikeprelevic from 1997, and there will be a reprise of his Missa di Natale (1998) by his former students of the Diaphonisches Vokalensemble in Cologne (see links at end of the posting). But Michael Vetter did much more than making music, and here I will put his creative life and his critical mind in a wider perspective than is usually done.

1. An outstanding and extremely productive visual artist

After spending many years of his youth already drawing and painting seriously, Vetter developed an extraordinary visual language of his own during the 1960s and 1970s, He used a wide range of techniques, from China ink drawings, paintings, watercolours and linocuts to ‘writing pieces’, perhaps his most far-fetching concept. Just like in music, Vetter was completely self-taught as a visual artist. Though he did of course absorb current techniques and styles, he drew much inspiration from Mediaeval techniques – a quite unfashionable source for artists in that period. His passion for great masters of the past was such, that as a teenager he already began collecting original Mediaeval volumes, which he apparently used as source material for his own techniques (he also kept hundreds of art books at home in recent years). If you ever heard Vetter talk about art – or read about his work in his own words – you know that his work was fully developed on a conceptual level: he was acutely aware of the peculiarities of all the major periods and styles in Western art of the second millennium, even of many artists and their development.

2. Laying the basis of Western/contemporary overtone singing

Of course, overtone singing would not look the same if Vetter had not helped to define its modern, Western style. He educated dozens of students that became singers in their own right (some of them well-known), and inspired many more – in fact he blew away many listeners, who had never heard such things before, including myself. Again, Vetter did not just perform a trick, or ‘just make sounds’, like many overtone singers are tempted to do. His melodic-harmonic approach to overtones betrays deeper connections, like with his great example Johann-Sebastian Bach. Few overtone singers are able to achieve such clarity of tone and such variety in the development of their compositions / improvisations as Vetter did. Besides setting an example with his NG-RR techniques (for singing lower and higher overtones, respectively), he produced extensive learning materials for his students and developed at least one unique way of singing overtones I never heard anyone do.

3. Beyond zen

Zen is too fashionable these days. You encounter the most obtuse uses of the word ‘zen’ in attempts to brand something as ‘spiritual’, ‘Asian’ and ‘cool’. Fortunately many people have also had genuine, first-hand zen experiences, among whom many artists. I think overall the transference of zen ideas to the West has led to some great artistic innovations. John Cage’s classes with the zen teacher Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki at Columbia University in the 1940s had far-reaching effects in every imaginable artistic discipline, well beyond the confines of his work as a composer. But Cage never sat cross-legged nor did he learn to meditate. Philip Glass, another big-name twentieth century composer who professed being influenced by Buddhism, did not have the kind of in-depth experiences that traditional students of Buddhism have. Vetter is one of few composers/musicians/artists who did go through the process more thoroughly. He observed daily morning meditations at his master’s shrine when he visited him, several months a year, while dedicating most his time to his own artistic work. He also spend several months a year at a monastery, where he took part in all the rituals, chanting, dressing up, begging for alms, et cetera.

For that reason, and for his superb grasp of art and aesthetics as a whole, I have high regard for the way he appropriated zen performing/visual art for his own artistic means. One of his best ideas is to transform the zen garden into a play, a dynamic process of moving and placing stones and other objects in an open-air surface. Another is his transformation of the okyo, the zen sutra’s. I will not go into those transformations here. Suffice it to say that the changes he made to these two zen traditions were well-informed, and in a way so much in tune with zen thought and practice, that they appear to be a logical step beyond traditional zen (as far as the overtone singing goes, monks disapproved when Vetter would slightly change the sound of his own okyos to amply certain harmonics).

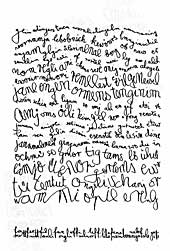

4. ‘The book of signs’: a 40+-year disciplined effort

Since 1972 or 1973 until his death, Vetter spent some time almost every day to work on a Magnus Opus of unusual breath: ‘Das Buch der Zeichen’ / ‘The Book of Signs’ (and that’s more than 40 years). In quick, improvised strokes, he would produce about 15-150 small China ink drawings. At the times I spend with him, he would do this after lunch. He carefully observed how the ink would flow, but as he continued to pull his brush across the paper, the ink would usually continue to flow. This would leave the final result undetermined by the time of his painting. He would continue to produce one drawing after another, mostly abstract, and pile them up while still wet. Then after 30 minutes or so, he would go through all the drawings one by one, carefully observing how the ink had settled. Like in some of his other work, it was his way of letting movement express itself, as it were, flowing through his hands not according to predetermined designs, but as an inevitable result of time unfolding. Each drawing is like a testimony of the flow of time expressed through spontaneous hand movements. I do it myself from time to time, like here, for example, as an ode to Michael. But I realised a few years ago, that if there is one thing I would wish I had (or could develop still), it was Michael’s discipline.

5. humour

O yes, you could have great laughs with Michael. He was full of wit, full of stories of his own adventures, of poems he could recite by heart (and certainly not the romantic ones, but absurd and perplexing ones). He had this mix of seriousness with lightness, bringing everything in balance again after the mind-boggling, or physically-straining or emotionally-charged practicing was done. In his work there were always these unexpected twists, which sometimes turned out very funny. He once told me a story of an invitation to an annual congress of recorder players. Vetter first made his name as an avant-garde recorder player, who completely redefined the instrument in the 1960s. Some of the greatest composers of our time wrote new pieces for him in the 1960s. But when Vetter was heralded as the former avant-garde innovator at the European Recorder Festival in 2006, he noticed that all the vigor had gone. The new generation of students played the radical works of the 1960s almost like classical pieces. What had been thrilling and upsetting 40 years earlier, now sounded tame. Vetter himself played one of J.S. Bach’s violin sonata’s on his recorder at the festival, but not without making the necessary adjustments in timing and phrasing, due to the transference of the piece from violin to recorded. This shocked many a conservative lover of Bach music, so much so, that just like in the 1960s, people left the concert hall, some of them protesting loudly. He recalled this episode with much enjoyment, and though it is not a typical example of Vetter’s humor as such, I treasure those moments when he would tell of all the strange and funny moments in his carreer – or simply tell a joke.

Find the links to the events here:

listen here to the radio-play DuO (click on the photo; introduction in German)