Last weekend Lin Xiao-Fen from Lin’s Culture held a benefit concert for the victims of the war in Ukraine, here in Taipei. On Friday the ticketsale closed now and a donation of 30k NT$ was sent to the war relief efforts. I was happy to be part of that and yet the sadness and mixed feelings were also taking over. I have many friends and acquaintances in Russia, a country that I have travelled to many times and where I hope to go back many times still. I was also shaped musically in part by the vibrant community of Russian and Ukrainian artists in Amsterdam during the 1990s. (For a short while, we played together in a band called Zodiac II). Many of them still live in Amsterdam and I can’t imagine the grief they must be sensing in the past six weeks – much less so of those who did not leave Ukraine. We all sense it.

It was hard to find the right words for it but being a vocalist and proposed to use an Alan Seeger poem as a leading idea, I had to sit down and figure out what to say. Many attempts to find the right words failed. But eventually I plainly told the story of how I once paid a short visit to the Ukraine. I dressed up in the clothes I had purchased at the Black Sea shore, probably the oldest clothes that I still have (and I can wear and keep clothes for very very long).

So here is what I said at the beginning of the performance:

˜ˆ˜ˆ`¨ˆ¨ˆ`˜˜ˆ˜ˆ¨˜`ˆ˜ˆ¨ˆ¨˜ˆ`¨ˆ¨ˆ`˜¨ˆ˜˜˜ˆ˜ˆ˜¨ˆ¨ˆ

Since around 1990 I was obsessed with the music of the Asian people from Tuva, in the heart of Siberia. I knew I had to try to go to Siberia, which at that time seemed like terra incognita.

In 1992 I began studying Russian in Moscow, where I lived with a family for 5 weeks. I got to know a guy called Yasha through the host family, and he became our money-changer, exchanging our US$ for Russian rubles at a good rate. After my intensive, daily training, he proposed we visit the Black Sea. We took the train. I had no visa for the Ukraine, but he said I just should keep quiet in case of inspections and we got to the Black Sea without a problem. There we took a swift hydrofoil to a nearby town, the name of which I cannot remember. What is engraved in my brain is this: we strolled out of town and approached an army base. I saw helicopters and fighter jets. Then we simply walked onto the army base. We got close to the helicopters. Some young soldiers or sailors came out. We chatted – I guess my friend had once served there and knew the place. Friendly, bored young men with nothing much to do. I admired the sailors’ suits. Before I knew it, one of them had walked into the barracks and came out with a suit for me. Some more hard currency changed hands.

OK, the Cold War was over, so much was clear. But I immediately sensed discomfort as the guy from the West. In the years that followed, back in Western Europe, I never liked the triumphalism I sensed around me towards the former Soviet states. I felt strange, and somewhat guilty, leading a life of abundance, while all across the former Soviet Union people struggled to establish a new economic and political order.

Meanwhile musicians arrived in the Netherlands from Siberia, and were astounded, or even in shock, at the sight of our supermarkets, packed with products. Not just milk, butter, and cheese. But 5 types of milk. 10 brands of butter. And 20 kinds of cheese.

The vulnerability of the former Soviet Union was all over the place. To me it felt wrong to unleash the aggressive tactics of neo-liberal capitalists of the so-called Free World to do their thing in Russia. The 1990s were messy for Russia, but who cared? Our model prevailed, time would teach them how to adopt democracy and free-market economy.

Did our own ignorance lead to the current tragedy? Were we too obsessed seeking pleasure, more wealth, more power on our own terms, under our own control, our own sphere of influence?

I never parted entirely from the sailor’s suit I traded for a few bucks at the Black Sea shore. It always signalled an uncomfortable realisation that we, the winners, did not care enough about those we saw as the losers.

˜ˆ˜ˆ`¨ˆ¨ˆ`˜˜ˆ˜ˆ¨˜`ˆ˜ˆ¨ˆ¨˜ˆ`¨ˆ¨ˆ`˜¨ˆ˜˜˜ˆ˜ˆ˜¨ˆ¨ˆ

In the end those were all the words I used during our improvisation. I did not use the Alan Seeger poem, which is beautiful indeed and poignant when you consider he lived out its content: he met his death very soon during World War I, in 1916.

I have a rendezvous with Death

Alan Seeger 1888 – 1916

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air—

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

It may be he shall take my hand

And lead me into his dark land

And close my eyes and quench my breath—

It may be I shall pass him still.

I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,

When Spring comes round again this year

And the first meadow-flowers appear.

God knows ’twere better to be deep

Pillowed in silk and scented down,

Where love throbs out in blissful sleep,

Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath,

Where hushed awakenings are dear…

But I’ve a rendezvous with Death

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

I thought it better to stick to my own experiences than to Alan Seeger’s. I had prepared fragments from a Tuvan epic as well but eventually, in the live situation, it did not feel appropriate to use that either. Instead, I merely put my intention on its message and started using kargyraa and khöömei combined with improvisations in a Tuvan, recitative manner.

I was joined by Guo Jing-Mu (郭靖沐) on guzheng, the bigger type of the Chinese zithers (and much louder than its sister, the seven-stringed guqin), and by Elizabeth Ditmanson on transverse flute.

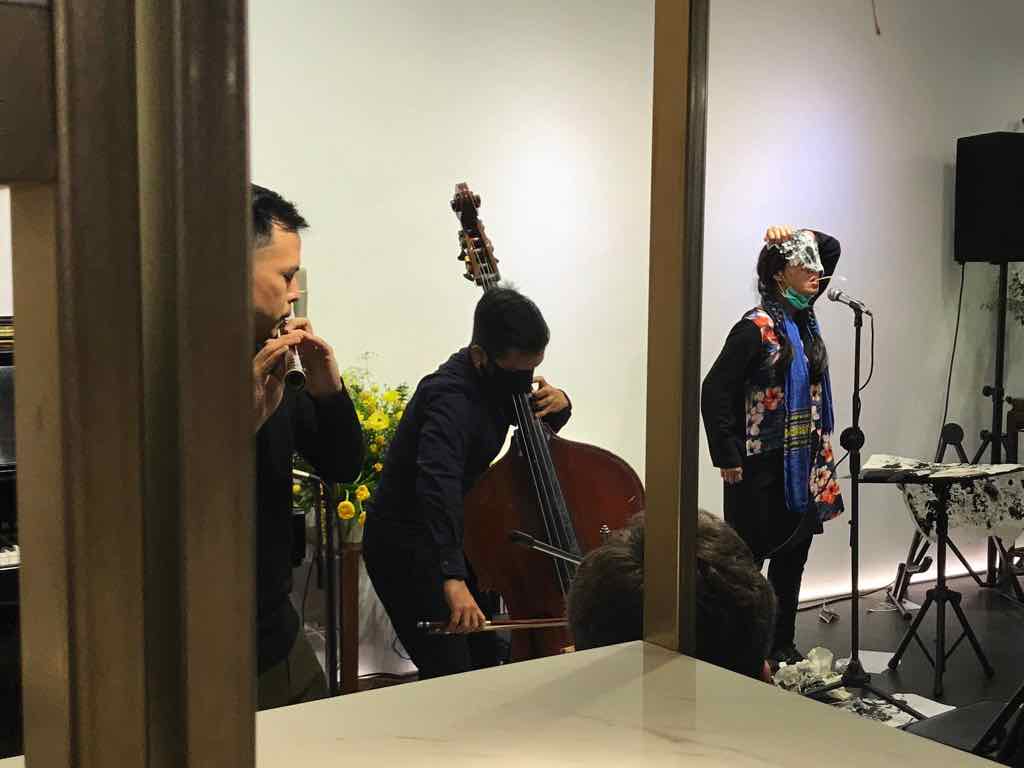

It was a gathering of some twenty improvisers, like you would normally see only over the course of multiple concerts or several days. I met or heard some musicians I had not met or heard before, but there were many old friends too. We were all eager to bring out the message to stop war, commemorating other tragedies like the 1896 Xincheng tragedy where local Taroko aboriginals were attacked by the Japanese rulers. Some were very dramatic performances indeed. I was deeply touched by the performance of composer I-Chin Li and his wife Chien-Chun Lin, with support from Xiao-Feng Lin on flute and Daniel Ditlevson on analog electronics (all pictured above). I-Chin and Chien-Chun played and sung something like a mini-opera, nearly completely improvised, and spoke out single words like ‘war’ and ‘love’. At the end Chien-Chun asked one more person to step forward. Her young daughter got up, unprepared, to just speak the word:

hope