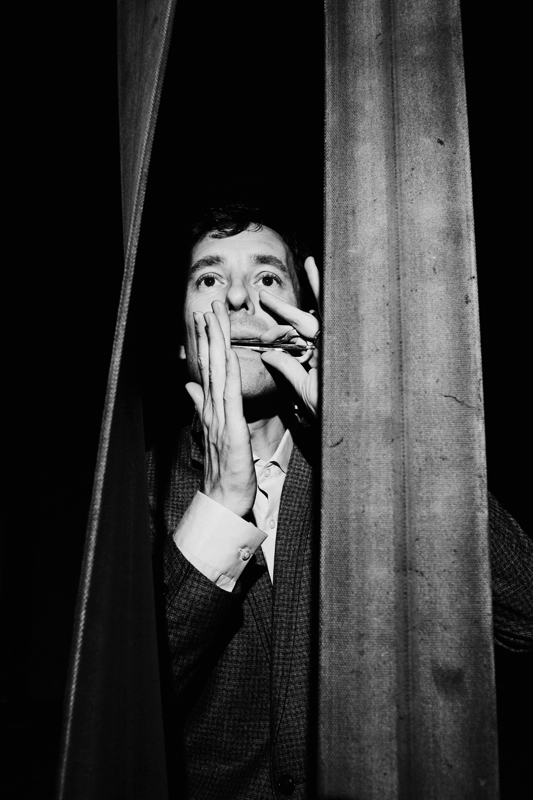

It is about time I start to teach some interesting musical instruments. The first workshop will be about Jew’s harps (also known as mouth harps): the small instrument you put against your teeth or lips to let it vibrate and then resonate in your mouth cavities. It is one of the most typical instruments in which harmonics or overtones are the main sound material you work with. But unlike overtone singing, it is very easy to learn the basics of the Jew’s harp (at least, for some types or models). And yet the Jew’s harp can be a musically challenging instrument too, inviting you while playing to discover more and more. It can be mystical and secretive, folksy and dance-like, serious and subtle, humorous and erotic… It is really like a semi-electronic version of the human voice, only not from the digital age but almost as old as humankind.

Some of my Jew’s harps, made of wood, bamboo, bronze, metal. All, except one, from Asia.

There are hundreds of varieties of Jew’s harps, which are indigenous to many peoples from the Eurasian plateau (Siberia, Europe, China, Central Asia), South and South-East Asia (Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, Philippines, Irian Jaya, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia), Polynesia and other places.

Let me divert a bit before continuing about the Jew’s harp (or scroll down for the workshop details). My interest in overtones stemmed from the question: what is sound colour? I wondered about this in the late 1980s as a musicology student (after being rejected by the conservatory). Soon enough I would focus most of attention to the voice and continue to do so, to the present day. But the quest for this neglected musical parameter timbre naturally extended to all kinds of instruments: Jew’s harps, musical bows and mouth bows, bells and gongs, didgeridoos, singing bowls, and basically any stringed and wind instrument, as long as it was played with multiphonics/overtones/colouristic changes. (Writing some 25 years after my quest started, things have improved quite a bit: many more textbooks dealing with music and sound now pay attention to the role of sound colour and overtones).

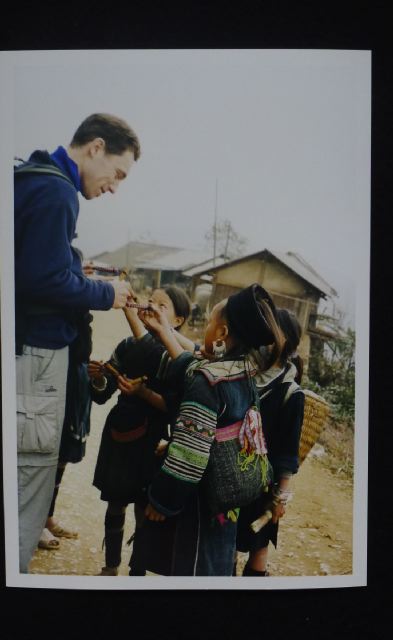

Young girls with indigenous Jew’s harps djam. They typically do not show the Jew’s harp they play. Sapa, Northern Vietnam. (photo: author, 2003)

From my ethonmusicology studies at the University of Amsterdam, I already heard quite a few interesting examples. I also closely followed a Dutch radio program, De Wandelende Tak, where travellers brought their recordings and stories from around the world: amazing first-hand material, often unpolished, raw, but ever so authentic and impressive because of the stories of the travellers (musicians, music anthropoligists, but also many others). And surely there was the third source: records! Already a vinyl-junky (more because of funk, soul, disco and jazz music than “traditional” music, up to that time), I scourched archives, libraries, second-hand record stores and markets, to find gems from faraway places.

For the question of sound colour I was particularly amazed by a set of records by The International Library of African Music (ILAM), with recordings collected and selectively issued by the great Hugh Tracey. Tracey was ahead of his time, a true academic dedicated to collect, preserve, compare, describe and analyse the vast musical universe of sub-Saharan Africa, without (post-)colonial tendencies such as thinking the music would be inferior to our Western music (the world at large still suffers from this problem…). I discovered the ILAM records in the once-famous Ethnomusicology Center Jaap Kunst at the music department where I studied. The Center included a sound archive with many rare items. The ILAM LPs came with small cards for each song, giving few details that would explain what these pieces were about and what the instruments were like.

It was mind-boggling to hear, and read about, the wealth of instruments that African musicians (often ‘ordinary people’) had produced. The entire southern part of Africa seemed to buzz with unusual timbres, overtones and noises. Together with the material I found from Mongolia, Siberia and Tibet, I felt that a great gap in my own Western musical background began to be filled (I only later fully realised that in Europe one can find just as many instrumental varieties and colours, if one looks back far enough). The rare African records which found their way only to some selected libraries around the world, have been reissued now, by a fellow-Dutchman and musician, Michael Baird, on his SWP label.

Hugh Tracey with his Sound of Africa and Music of Africa LPs*

Hugh Tracey with his Sound of Africa and Music of Africa LPs*

Most of the instruments I learned about while exploring timbre and overtones, I have never seen or learnt to play. There are some exceptions: I have been fiddling around with the Vietnamese dan bau (a special kind of monochord or one-stringed zither found only in Vietnam), the didgeridoo (yedaki in one of the indigenous terms), the igil or horse-head fiddle from Tuva, gongs, singing bowls and musical bows and mouth bows of the Xhosa.

Dan Bau (Vietnamese monochord)

Xhosa musicians (South Africa) with umrubhe mouth bows (third and fourth from left). Photo: author

But back to the Jew’s harp! I took to this instrument more seriously, because it is so prominent in Siberia,where I began to do much of my fieldwork. It is also easier to play, to carry around (like your voice) and to collect (Jew’s harp prices range from very cheap to very affordable). There are very fine examples of Jew’s harps produced and played in Tuva, the Altai and more robust from Sakha (or Yakutia), which is the world’s leading Jew’s harp ‘nation’ (the Jew’s harp is the national symbol of the Yakut people). Recently the irregular International Jew’s Harp Festival was held in Sakha: at that occasion more than 1300 players were recorded, playing simultaneously.

To hear how one of them sounds alone, have a look at one of the stars of contemporary Sakha Jew’s harp culture, Albina Degtyareva, playing her piece The legend of the creation of the world. (you can see her playing in the above video as well).

Obviousy, what she does is very difficult. Mrs. Degtyareva plays what I call the Rolls Royce of the Jew’s harps, a top model made by master makers from Yakutia. Not quite the right model to start with. We will start learning with the Vietnamese djam/dan moi, the most easy type of all Jew’s harps, with a very crisp, beautiful sound.

WORKSHOP

In the one-day workshop you will get to know the Jew’s harp and learn to play it. You place it in front of the lips or against the teeth. It has a thin lamella, attached to a frame. After plucking it, it starts to vibrate back and forth between the teeth and/or lips, producing tones of many frequencies. The colour of the tones are defined by overtones or harmonics which can be clearly heard, and which change when the shape of the mouth is changed.

Although Taiwan boasts some of the most extraordinary Jew’s harps, made and played by the Tayal people, we will learn to play the Jew’s harp from a mountain tribe of Northern Vietnam, the Hmong. Their Jew’s harp is called djam, more populary known by its Vietnamese name, dan moi. In 2003 I traveled to Vietnam and witnessed the local Hmong musicians play Jew’s harps. I also purchase some original instruments from them. Nowadays most djam are produced by Vietnamese makers in the bigger cities, such as Hanoi.

Tuvan xomus (left) and Vietnamese djam made by Hmong makers (right),

with their cases. photo: author

During the workshop every student will get a djam to practice which you can take home afterwards, so you can continue to learn by yourself. During the day you will get to know basic techniques of playing the Jew’s harp and learn a lot about the cultures around this instrument in traditional, contemporary, folk, pop and art music. We will listen to recordings and I will play live examples of different Jew’s harps.

At the end of the day

* you have learned about an instrument you a) did not even know it existed or b) thought to be very exotic

* you will be able to actually play a new instrument yourself and

* you can bring it home with you.

Djam made by Vietnamese (Kinh) makers.

For whom: Anyone curious about music traditions, sound and voice, and learning to play a new instrument. No previous musical experience required.

Age: 10 and up

Language: English (with Chinese translation)

Date/Time : 18 October 2015. Time: 10 AM – 5 PM (Lunchbreak on your own (1-2 PM).

Place: Canjune Training Center, Daan

Price: 1500 NT$

Discounts: students 20% (bring your ID); a parent with a kid 20 % (3000 – 600 = 2400).

Interested? Get more inquiries from Mark (info@fusica.nl) or Yvonne (chichenlyv@gmail.com) or just register and we’ll send you the payment details. Or call us: 0910382749 / 0933178272.

Next workshop: Sound Journey: Art of Listening (Hsinchu, October 31/November 1)

Next next workshop: Vetter-Transverbal (Taipei, December 20)

In Sapa, Vietnam, 2003.

* Photo source: Diane Thram, ‘Performing the archive: The ILAM For Future Generations exhibit, Music Heritage Project SA and Red Location Music History Project’, IASPM 2011 Proceedings.