HYPNOKYO

or how to combine the art of writing meaningful non-sense texts with hypnosis methods

Next week I am teaching a group of hypnosis students in Taipei. They are the students of a man who goes by the nickname of La Mian (ramen, or Japanese thick noodles) who is specialized in hypnosis and teaches and applies it in a wide range of methods. He came to my workshop Ocean of Voices recently, a 3-day exploration of the richness of musical traditions around the world (focusing on the voice). We had several amazing sessions where everyone went through his or her own transformations while singing, chanting, drumming, playing, or just listening to everyone else. Paths to change the body, change the mind and empower your creative imagination through the voice: a dynamic key or bridge that sits in between the body and mind, working its logical and illogical ways in both directions.

Photos taken during the Oceaen of Voices of workshop in Nantou, Taiwan. Above, La Mian with the Bunun people from XinYi. Below, session during the workshop.

You could call the logical part the verbal: the voice as speech, as reason and gossip.

You could call the illogical part transverbal: the voice as sound and music, as noise and non-sense.

Transverbal is a term Michael Vetter coined to group together, and give purpose to, his vast corpus of creative work, in music, in visual arts, in writing. It led, among other things, to his writing of okyo’s, which is Japanese for sutras. His sutras were not Buddhist texts, but used the sounds of the Japanese language as a template from which he created ‘texts’ without meaning. It was not merely a capricious thing, a joke, or an anti-religious sentiment. Vetter was serious about it. He had practised chanting and reciting actual sutras for year after year during his 13 year stay in Japan, going about the streets begging for alms or performing ceremonial. But, in a true Zen vein, he would not eschew the occasional humorous twist in his own okyos either.

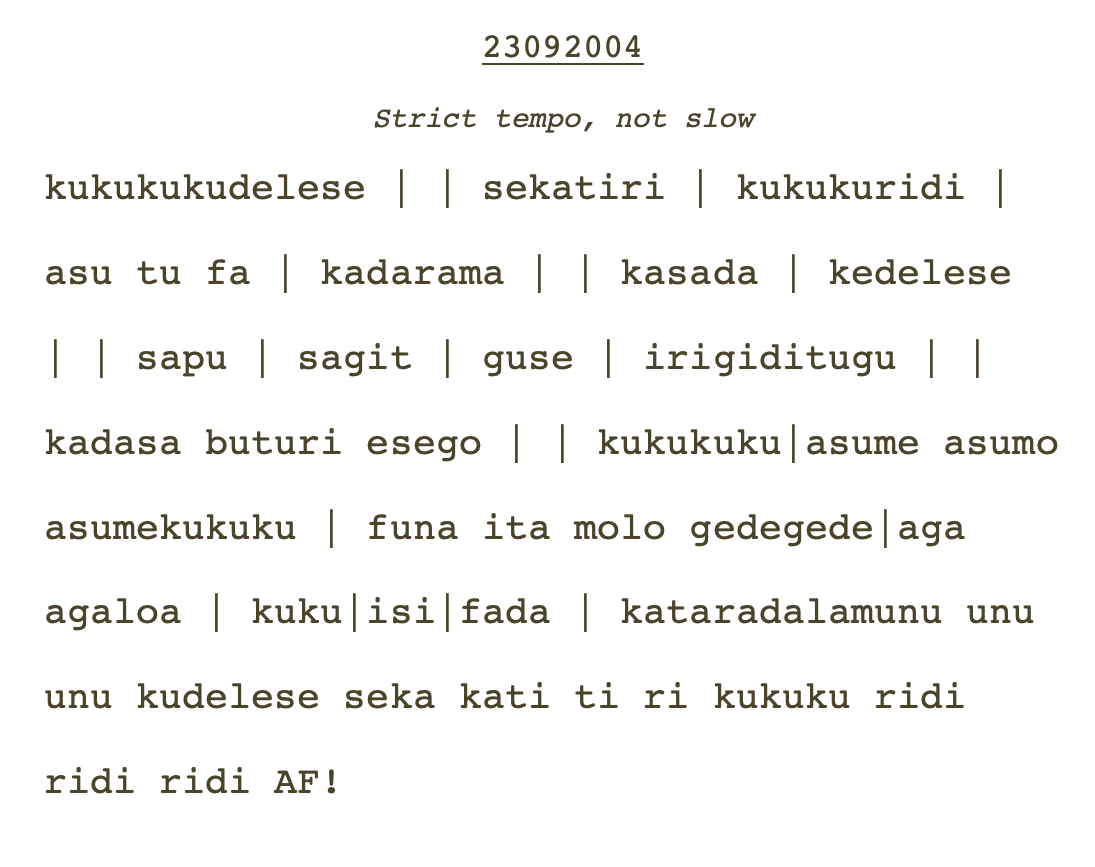

I got to know Michael Vetter’s okyos in the mid 1990s and was impressed with their form and sound and Vetter’s precise reasoning for why he created them. Later I began to write my own occasional okyos. Last year I decided to write an okyo every day for one year, to commemorate Michael’s birth (in 1943) and passing (in 2013), now eighty and ten years ago. I shape these okyos, naturally, but they also shape me, and invite me or teach me to push for new ideas about sound, language and symbol. Here is one example which I will take to the Hypnokyo workshop:

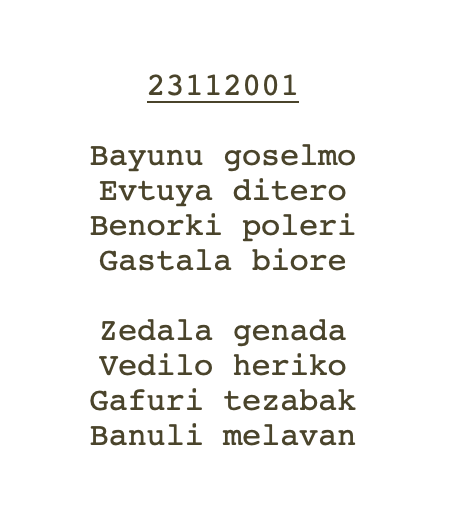

Here is another one

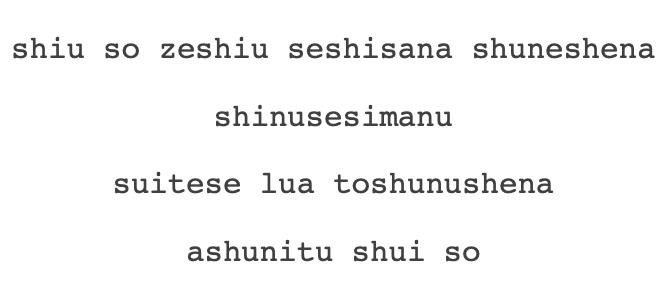

And here is one that you can listen to in the video, below:

So next week my okyos are going to be tested by students of hypnosis. They learn a range of sounding techniques that could enhance or expand their hypnosis practise. I am really looking forward to see what they will do with it, and hope I can be their guinea pig to test the efficacy of the okyos. Not long ago, hypnosis was regarded as somewhat occult, esoteric and strange. In recent years it has become more widely accepted and it began to loose its strangeness in public opinion. The approach now seems to be more practical: it is yet another way for us – complicated, sensitive and often limited and hyperrational human beings – to understand the mysteries of life and self, and to make sense of the world around us in new, more attuned ways.

You can enjoy listening to one of my okyos in this video (thanks to Sky for editing).

And I will read this week’s episode of one of my favorite newsletters, which happens to be devoted to clinical hypnosis.

Here is another one

Here is another one